publications

2025

-

Same data, different analysts: variation in effect sizes due to analytical decisions in ecology and evolutionary biologyGould E., ... ..., Martin Bulla, and 1 more author2025

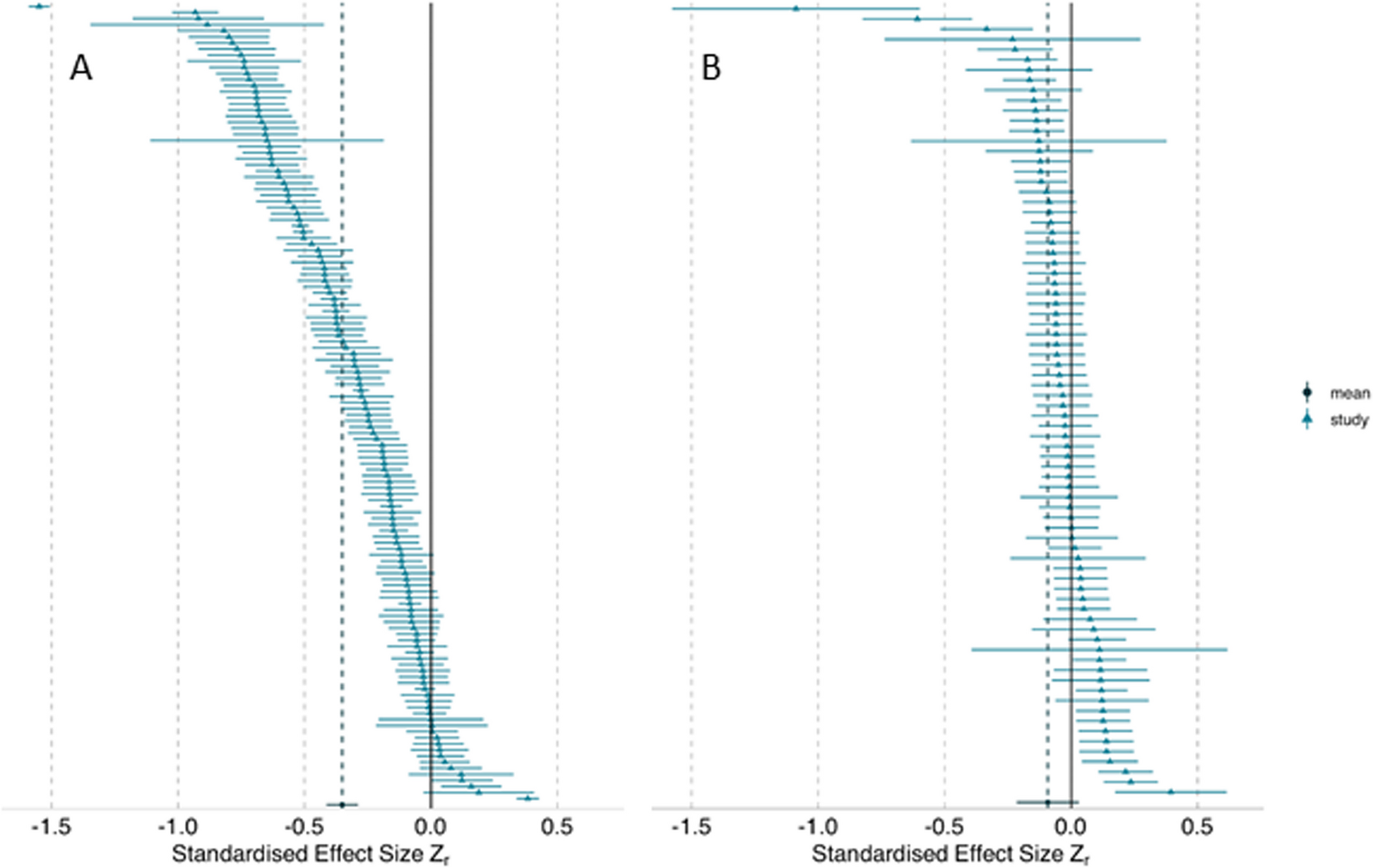

Same data, different analysts: variation in effect sizes due to analytical decisions in ecology and evolutionary biologyGould E., ... ..., Martin Bulla, and 1 more author2025Although variation in effect sizes and predicted values among studies of similar phenomena is inevitable, such variation far exceeds what might be produced by sampling error alone. One possible explanation for variation among results is differences among researchers in the decisions they make regarding statistical analyses. A growing array of studies has explored this analytical variability in different fields and has found substantial variability among results despite analysts having the same data and research question. Many of these studies have been in the social sciences, but one small “many analyst” study found similar variability in ecology. We expanded the scope of this prior work by implementing a large-scale empirical exploration of the variation in effect sizes and model predictions generated by the analytical decisions of different researchers in ecology and evolutionary biology. We used two unpublished datasets, one from evolutionary ecology (blue tit, Cyanistes caeruleus, to compare sibling number and nestling growth) and one from conservation ecology (Eucalyptus, to compare grass cover and tree seedling recruitment). The project leaders recruited 174 analyst teams, comprising 246 analysts, to investigate the answers to prespecified research questions. Analyses conducted by these teams yielded 141 usable effects (compatible with our meta-analyses and with all necessary information provided) for the blue tit dataset, and 85 usable effects for the Eucalyptus dataset. We found substantial heterogeneity among results for both datasets, although the patterns of variation differed between them. For the blue tit analyses, the average effect was convincingly negative, with less growth for nestlings living with more siblings, but there was near continuous variation in effect size from large negative effects to effects near zero, and even effects crossing the traditional threshold of statistical significance in the opposite direction. In contrast, the average relationship between grass cover and Eucalyptus seedling number was only slightly negative and not convincingly different from zero, and most effects ranged from weakly negative to weakly positive, with about a third of effects crossing the traditional threshold of significance in one direction or the other. However, there were also several striking outliers in the Eucalyptus dataset, with effects far from zero. For both datasets, we found substantial variation in the variable selection and random effects structures among analyses, as well as in the ratings of the analytical methods by peer reviewers, but we found no strong relationship between any of these and deviation from the meta-analytic mean. In other words, analyses with results that were far from the mean were no more or less likely to have dissimilar variable sets, use random effects in their models, or receive poor peer reviews than those analyses that found results that were close to the mean. The existence of substantial variability among analysis outcomes raises important questions about how ecologists and evolutionary biologists should interpret published results, and how they should conduct analyses in the future.

@article{RN7800, author = {E., Gould and ..., ... and Bulla, Martin and et, al}, title = {Same data, different analysts: variation in effect sizes due to analytical decisions in ecology and evolutionary biology}, journal = {BMC Biology}, doi = {10.1186/s12915-024-02101-x}, year = {2025}, osf = {https://github.com/egouldo/ManyEcoEvo/}, preprint = {https://doi.org/10.32942/X2GG62}, type = {Journal Article} } -

No support for honest signalling of male quality in zebra finch song.Martin Bulla, Remya Sankar, and Wolfgang Forstmeier2025

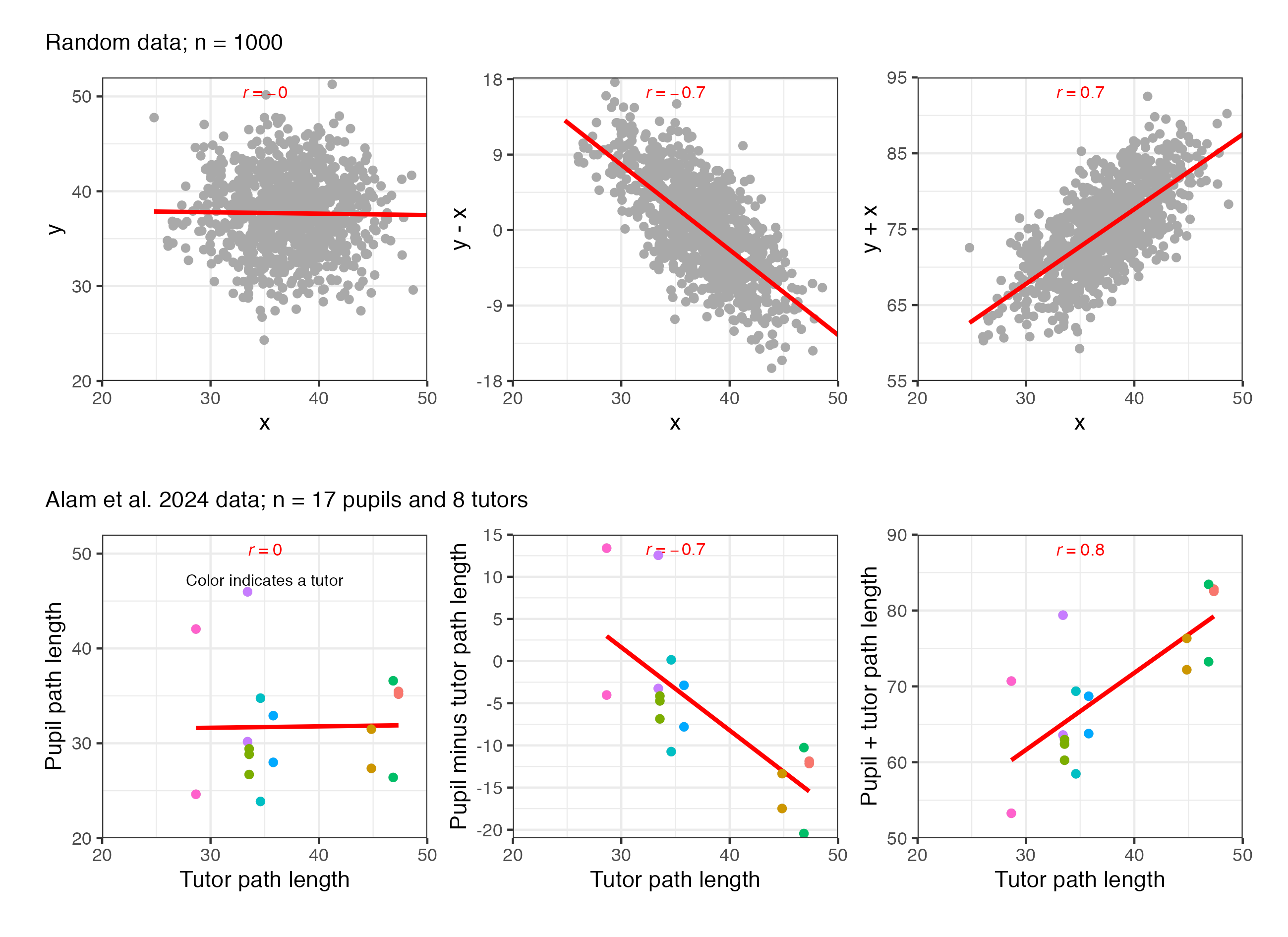

No support for honest signalling of male quality in zebra finch song.Martin Bulla, Remya Sankar, and Wolfgang Forstmeier2025Alam et al.1 claim to have discovered a song feature, “path length”, that honestly signals male fitness and is therefore preferred by all females. However, their data and analyses provide no statistical support for this claim. (1) The key finding — that long-path songs are difficult to learn (Fig. 4c) — is a statistical artefact: regressing y minus x on x creates an illusory effect where none exists. (2) Their path-length estimates have a measurement error of 45-73%, which undermines their conclusions, including the claim that females prefer long-path songs. (3) This claim is based on playback experiments that use only three artificial stimulus pairs, which, given the measurement error, cannot reliably contrast long and short paths. In sum, there is no evidence that path length functions as an honest fitness indicator. Our re-evaluation highlights the importance of validating new methods and accounting for random noise in small datasets. Finally, we emphasise that in species where females are known to disagree on who is attractive2-6, searching for a trait that determines male attractiveness is unwarranted.

@article{RN7799, author = {Bulla, Martin and Sankar, Remya and Forstmeier, Wolfgang}, journal = {EcoEvoArxiv}, doi = {10.1186/s12915-024-02101-x}, year = {2025}, osf = {https://github.com/MartinBulla/rebuttal_alam_2024}, preprint = {https://doi.org/10.32942/X2D324}, type = {Journal Article} }

2024

-

Urban birds’ flight responses were unaffected by the COVID-19 shutdownsPeter Mikula, Martin Bulla, Daniel Blumstein, and 13 more authors2024

Urban birds’ flight responses were unaffected by the COVID-19 shutdownsPeter Mikula, Martin Bulla, Daniel Blumstein, and 13 more authors2024The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has dramatically altered human activities, potentially relieving human pressures on urban-dwelling animals. Here, we evaluated whether birds from five cities in five countries (Czech Republic – Prague, Finland – Rovaniemi, Hungary – Budapest, Poland – Poznan, and Australia – Melbourne) changed their tolerance towards human presence (measured as flight initiation distance) during the COVID-19 shutdowns. We collected 6369 flight initiation distance estimates for 147 bird species and found that birds tolerated approaching humans to a similar level before and during the COVID-19 shutdowns. Moreover, during the shutdowns, bird escape behaviour did not consistently change with the level of governmental restrictions (measured as the stringency index). Hence, our results indicate that birds do not flexibly and quickly adjust their escape behaviour to the reduced human presence; in other words, the breeding populations of urban birds examined might already be tolerant of human activity and perceive humans as relatively harmless.

@article{RN7795, author = {Mikula, Peter and Bulla, Martin and Blumstein, Daniel and Benedetti, Yanina and Floigl, Kristina and Jokimaki, Jukka and Kaisanlahti-Jokimaki, Marja-Liisa and Marko, Gabor and Morelli, Federico and Moller, Anders Pape and Siretckaia, Anastasiia and Szakony, Sara and Weston, Michael and Zeid, Farah Abou and Tryjanowski, Piotr and Albrecht, Tomas}, title = {Urban birds' flight responses were unaffected by the COVID-19 shutdowns}, journal = {Communications Biology}, doi = {10.1101/2022.07.15.500232}, year = {2024}, osf = {https://martinbulla.github.io/avian_FID_covid/}, preprint = {https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.15.500232v1.full}, type = {Journal Article} } -

Sperm swimming speed and morphology differ slightly among the three genetic morphs of ruff sandpiper (Calidris pugnax), but show no clear polymorphismMartin Bulla, Clemens Küpper, David B Lank, and 9 more authors2024

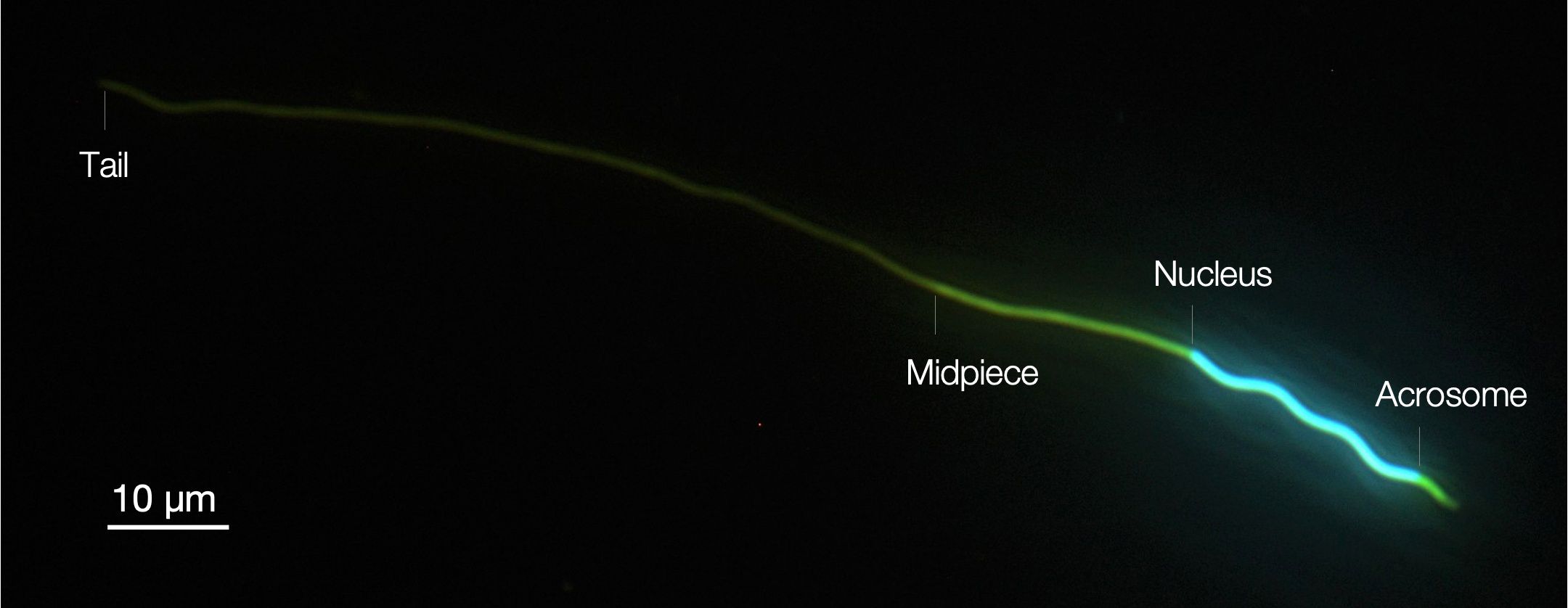

Sperm swimming speed and morphology differ slightly among the three genetic morphs of ruff sandpiper (Calidris pugnax), but show no clear polymorphismMartin Bulla, Clemens Küpper, David B Lank, and 9 more authors2024The ruff sandpiper (Calidris pugnax) is a lekking shorebird with three male morphs that differ remarkably in behavior, ornaments, size, and endocrinology. The morphs are determined by an autosomal inversion. Aggressive Independents evolved first, female-mimicking Faeders 4 mil year ago when a short segment of a chromosome reversed in orientation, and semi-cooperative Satellites 70,000 years ago through a recombination of the Independent and Faeder inversion-segment genotypes. Although the genetic differences between the morphs affect numerous phenotypic traits, it is unknown whether they also affect sperm traits. Here, we use a captive-bred population of ruffs to compare ruff sperm to that of other birds and compare sperm swimming speed and morphology among the morphs. Ruff sperm resembled those of passerines, but moved differently. Faeder sperm moved the slowest and had the longest midpiece. Independents’ sperm were neither the fastest nor the least variable, but had the shortest tail and midpiece. Although the midpiece contains the energy-producing mitochondria, its length was not associated with sperm swimming speed. Instead, two of three velocity metrics weakly positively correlated with head length (absolute and relative). We conclude that there is an indication of quantitative differences in sperm between morphs, but no clear sperm polymorphism.

@article{RN7796, author = {Bulla, Martin and K{\"u}pper, Clemens and Lank, David B and Albrechtov{\'a}, Jana and Loveland, Jasmine L and Martin, Katrin and Teltscher, Kim and Cragnolini, Margherita and Lierz, Michael and Albrecht, Tom{\'a}{\v s} and Forstmeier, Wolfgang and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Sperm swimming speed and morphology differ slightly among the three genetic morphs of ruff sandpiper (Calidris pugnax), but show no clear polymorphism}, journal = {Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution}, doi = {10.3389/fevo.2024.1476254}, year = {2024}, preprint = {https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.27.550846}, type = {Journal Article} }

2022

-

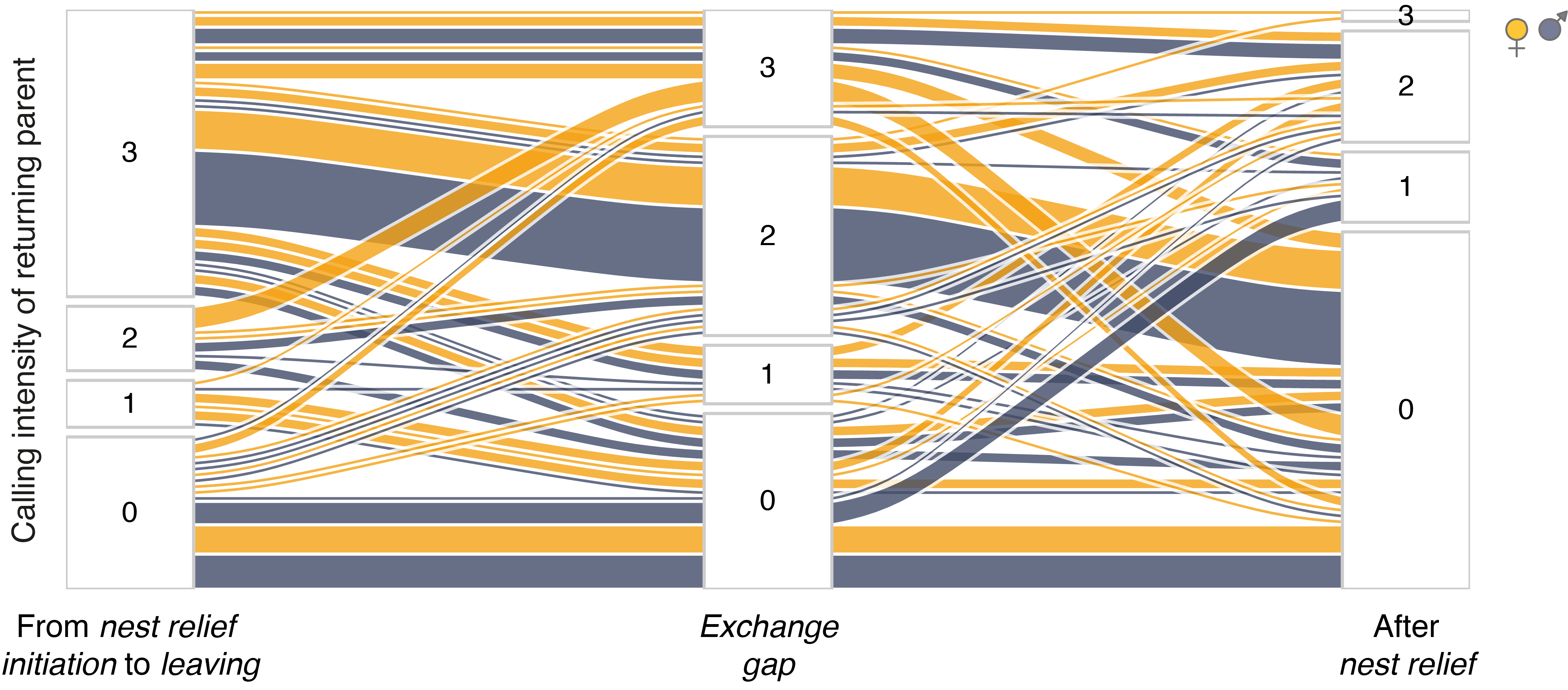

Nest reliefs in a cryptically incubating shorebird are quick, but vocalMartin Bulla, Christina Muck, Daniela Tritscher, and 1 more author2022

Nest reliefs in a cryptically incubating shorebird are quick, but vocalMartin Bulla, Christina Muck, Daniela Tritscher, and 1 more author2022In species with biparental care, coordination of parental behaviour between pair members increases reproductive success. Coordination is difficult if opportunities to communicate are scarce, which might have led to the evolution of elaborate nest relief rituals in species facing a low predation risk. However, whether such conspicuous rituals also evolved in species that avoid predation by relying on crypsis remains unclear. Here, we used a continuous monitoring system to describe nest relief behaviour during incubation in an Arctic-breeding shorebird with passive nest defence, the Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla. We also explored whether behaviour of exchanging parents informs about parental coordination and predicts incubation effort. We found that incubating parents vocalized twice as much before the arrival of their partner than during other times of incubation. In at least 75% of exchanges, the incubating parent left the nest only after its partner had returned and initiated the nest relief. In these cases, exchanges were quick (25 s, median) and shortened over the incubation period by 0.1–1.4 s/day (95% CI), suggesting that parents became more synchronized. However, nest reliefs were not cryptic. In 90% of exchanges, at least one parent vocalized, and in 20% of nest reliefs the incubating parent left the nest only after its returning partner called incessantly. In 27% of cases, the returning parent initiated the nest relief with a call; in 39% of these cases, the incubating partner replied. If the partner replied, its following off-nest bout was 1–4 h (95% CI) longer than when the partner did not reply, which corresponds to an 8–45% increase. Our results indicate that incubating Semipalmated Sandpipers, which rely on crypsis to avoid nest predation, have quick but acoustically conspicuous nest reliefs. Our results also suggest that vocalizations during nest reliefs may be important for the coordination and division of parental duties.

@article{RN7745, author = {Bulla, Martin and Muck, Christina and Tritscher, Daniela and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Nest reliefs in a cryptically incubating shorebird are quick, but vocal}, journal = {Ibis}, issn = {0019-1019 1474-919X}, doi = {10.1111/ibi.13069}, year = {2022}, osf = {https://osf.io/e2w7y/}, preprint = {https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2023/07/30/2023.07.27.550846}, type = {Journal Article} } -

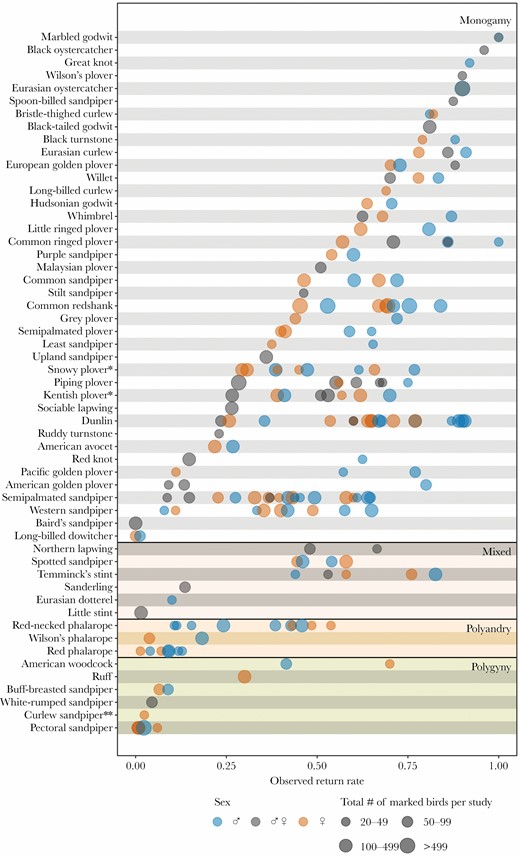

Breeding site fidelity is lower in polygamous shorebirds and male-biased in monogamous speciesEunbi Kwon, Mihai Valcu, Margherita Cragnolini, and 4 more authors2022

Breeding site fidelity is lower in polygamous shorebirds and male-biased in monogamous speciesEunbi Kwon, Mihai Valcu, Margherita Cragnolini, and 4 more authors2022Sex-bias in breeding dispersal is considered the norm in many taxa, and the magnitude and direction of such sex-bias is expected to correlate with the social mating system. We used local return rates in shorebirds as an index of breeding site fidelity, and hence as an estimate of the propensity for breeding dispersal, and tested whether variation in site fidelity and in sex-bias in site fidelity relates to the mating system. Among 111 populations of 49 species, annual return rates to a breeding site varied between 0% and 100%. After controlling for body size (linked to survival) and other confounding factors, monogamous species showed higher breeding site fidelity compared with polyandrous and polygynous species. Overall, there was a strong male bias in return rates, but the sex-bias in return rate was independent of the mating system and did not covary with the extent of sexual size dimorphism. Our results bolster earlier findings that the sex-biased dispersal is weakly linked to the mating system in birds. Instead, our results show that return rates are strongly correlated with the mating system in shorebirds regardless of sex. This suggests that breeding site fidelity may be linked to mate fidelity, which is only important in the monogamous, biparentally incubating species, or that the same drivers influence both the mating system and site fidelity. The strong connection between site fidelity and the mating system suggests that variation in site fidelity may have played a role in the coevolution of the mating system, parental care, and migration strategies.

@article{RN7658, author = {Kwon, Eunbi and Valcu, Mihai and Cragnolini, Margherita and Bulla, Martin and Lyon, Bruce and Kempenaers, Bart and Jennions, Michael D.}, title = {Breeding site fidelity is lower in polygamous shorebirds and male-biased in monogamous species}, journal = {Behavioral Ecology}, issn = {1045-2249 1465-7279}, doi = {10.1093/beheco/arac014}, year = {2022}, type = {Journal Article} }

2021

-

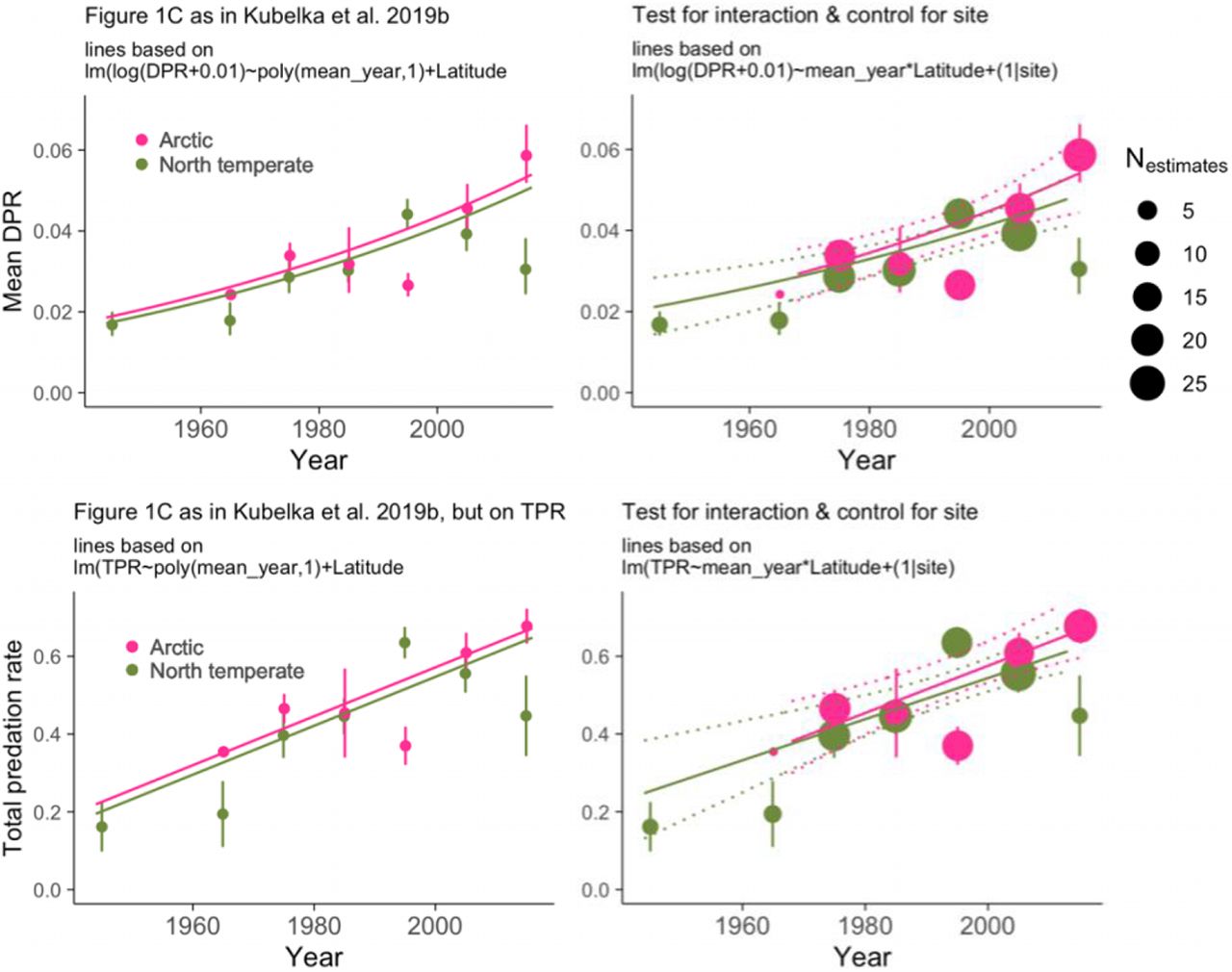

Still no evidence for disruption of global patterns of nest predation in shorebirdsMartin Bulla, Mihai Valcu, and Bart Kempenaers2021

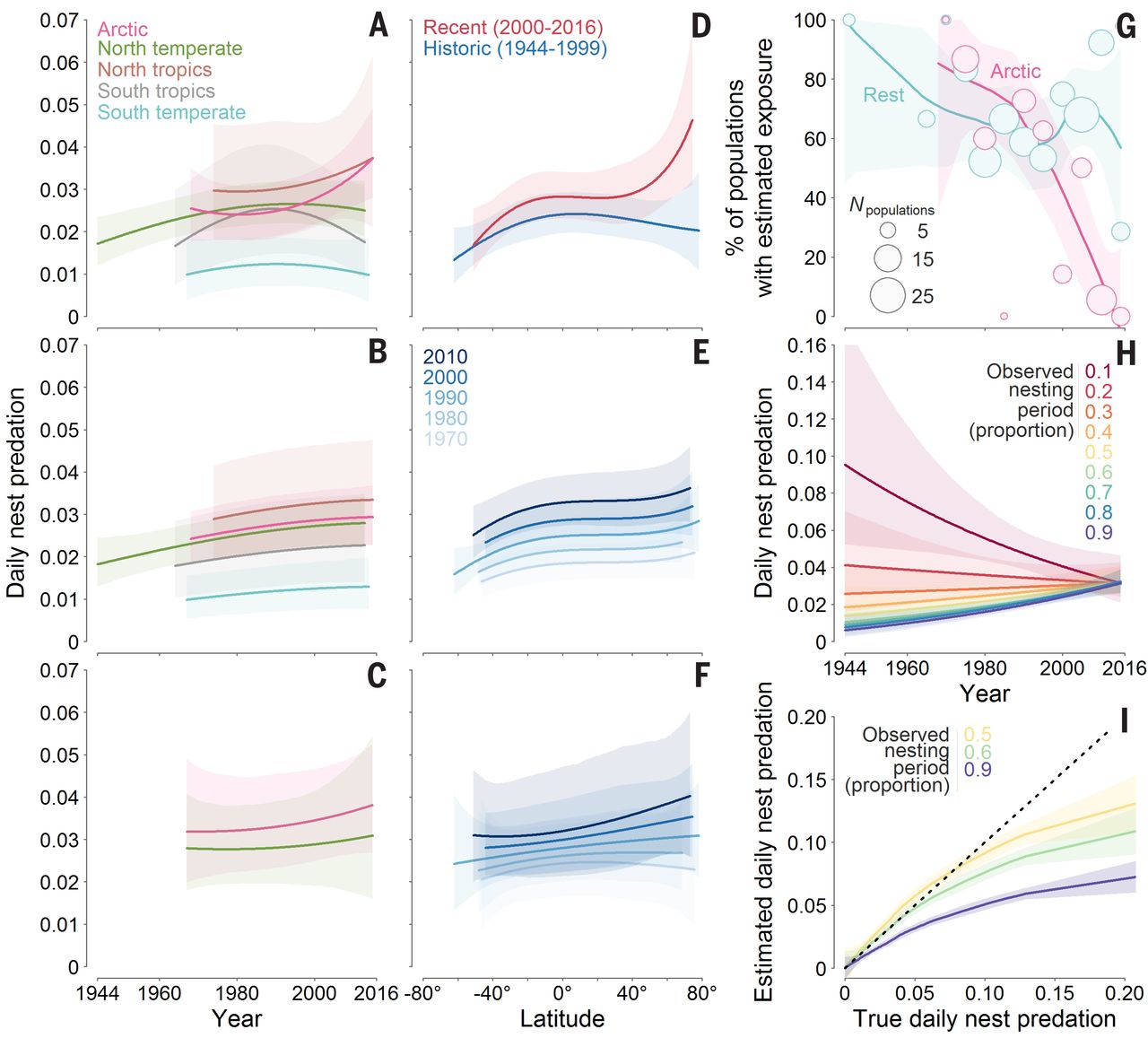

Still no evidence for disruption of global patterns of nest predation in shorebirdsMartin Bulla, Mihai Valcu, and Bart Kempenaers2021Many shorebird species are rapidly declining (Piersma et al. 2016; Munro 2017; Studds et al. 2017), but it is not always clear why. Deteriorating and disappearing habitat, e.g. due to intensive agriculture (Donal et al. 2001; Kentie et al. 2013; Kentie et al. 2018), river regulation (Nebel et al. 2008) or mudflat reclamation (Ma et al. 2014; Larson 2017), and hunting (Reed et al. 2018; Gallo-Cajiao et al. 2020) are some of the documented causes. A recent study suggests yet another possible cause of shorebird decline: a global increase in nest predation (Kubelka et al. 2018). The authors compiled an impressive dataset on patterns of nest predation in shorebirds and their analyses suggest that global patterns of nest predation have been disrupted by climate change, particularly in the Arctic. They go as far as to conclude that the Arctic might have become an ecological trap (Kubelka et al. 2018). Because these findings might have far-reaching consequences for conservation and related political decisions, we scrutinized the study and concluded that the main conclusions of Kubelka et al. (2018) are invalid (Bulla et al. 2019a). The authors then responded by reaffirming their conclusions (Kubelka et al. 2019b). Here, we evaluate some of Kubelka et al.’s (2019b) responses, including their recent erratum (2020), and show that the main concerns about the original study still hold. Specifically, (1) we reaffirm that Kubelka et al.’s (2018) original findings are confounded by study site. Hence, their conclusions are over-confident because of pseudo-replication. (2) We reiterate that there is no statistical support for the assertion that predation rate has changed in a different way in the Arctic compared to other regions. The relevant test is an interaction between a measure of time (year or period) and a measure of geography (e.g., Arctic vs the rest of the world). The effect of such an interaction is weak, uncertain and statistically non-significant, which undermines Kubelka et al.’s (2018) key conclusion. (3) We further confirm that the suggested general increase in predation rates over time is at best a weak and uncertain trend. The most parsimonious hypothesis for the described results is that the temporal changes in predation rate are an artefact of temporal changes in methodology and data quality. Using only high-quality data, i.e. directly calculated predation rates, reveals no overall temporal trend in predation rate. Below we elaborate in detail on each of these points. We conclude that (i) there is no evidence whatsoever that the pattern in the Arctic is different from that in the rest of the world and (ii) there is no solid evidence for an increase in predation rate over time. While we commend Kubelka et al. for compiling and exploring the data, we posit that the data underlying their study, and perhaps all currently available data, are not sufficient (or of sufficient quality) to test their main hypotheses. We call for standardized and consistent data collection protocols and experimental validation of current methods for estimating nesting success.

@article{RN7179, author = {Bulla, Martin and Valcu, Mihai and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Still no evidence for disruption of global patterns of nest predation in shorebirds}, journal = {Science}, doi = {https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.17.431576}, year = {2021}, osf = {https://github.com/MartinBulla/Still_no_evidence/}, type = {Journal Article} } -

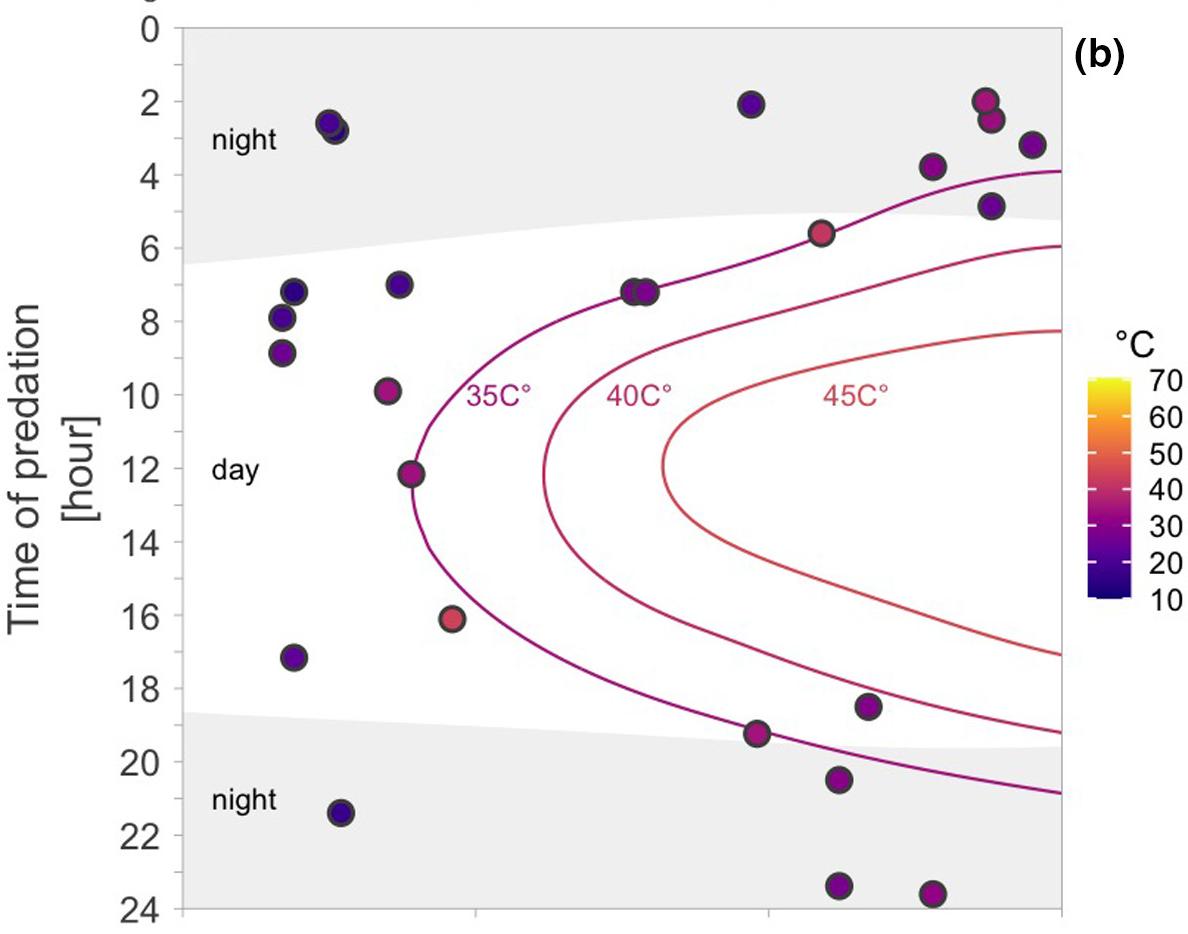

Diel timing of nest predation changes across breeding season in a subtropical shorebirdMartin Sládeček, Kateřina Brynychová, Esmat Elhassan, and 8 more authors2021

Diel timing of nest predation changes across breeding season in a subtropical shorebirdMartin Sládeček, Kateřina Brynychová, Esmat Elhassan, and 8 more authors2021Predation is the most common cause of nest failure in birds. While nest predation is relatively well studied in general, our knowledge is unevenly distributed across the globe and taxa, with, for example, limited information on shorebirds breeding in subtropics. Importantly, we know fairly little about the timing of predation within a day. Here, we followed 444 nests of the red-wattled lapwing (Vanellus indicus), a ground-nesting shorebird, for a sum of 7,828 days to estimate a nest predation rate, and continuously monitored 230 of these nests for a sum of 2,779 days to reveal how the timing of predation changes over the day and season in a subtropical desert. We found that 312 nests (70%) hatched, 76 nests (17%) were predated, 23 (5%) failed for other reasons, and 33 (7%) had an unknown fate. Daily predation rate was 0.95% (95%CrI: 0.76% – 1.19%), which for a 30-day long incubation period translates into 25% (20% – 30%) chance of nest being predated. Such a predation rate is low compared to most other avian species. Predation events (N = 25) were evenly distributed across day and night, with a tendency for increased predation around sunrise, and evenly distributed also across the season, although night predation was more common later in the season, perhaps because predators reduce their activity during daylight to avoid extreme heat. Indeed, nests were never predated when midday ground temperatures exceeded 45℃. Whether the diel activity pattern of resident predators undeniably changes across the breeding season and whether the described predation patterns hold for other populations, species, and geographical regions await future investigations.

@article{RN7319, author = {Sládeček, Martin and Brynychová, Kateřina and Elhassan, Esmat and Šálek, Miroslav E. and Janatová, Veronika and Vozabulová, Eva and Chajma, Petr and Firlová, Veronika and Pešková, Lucie and Almuhery, Aisha and Bulla, Martin}, title = {Diel timing of nest predation changes across breeding season in a subtropical shorebird}, journal = {Ecology and Evolution}, volume = {11}, number = {19}, issn = {2045-7758 2045-7758}, doi = {https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8025}, year = {2021}, osf = {https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BQ4DR}, type = {Journal Article} }

2020

-

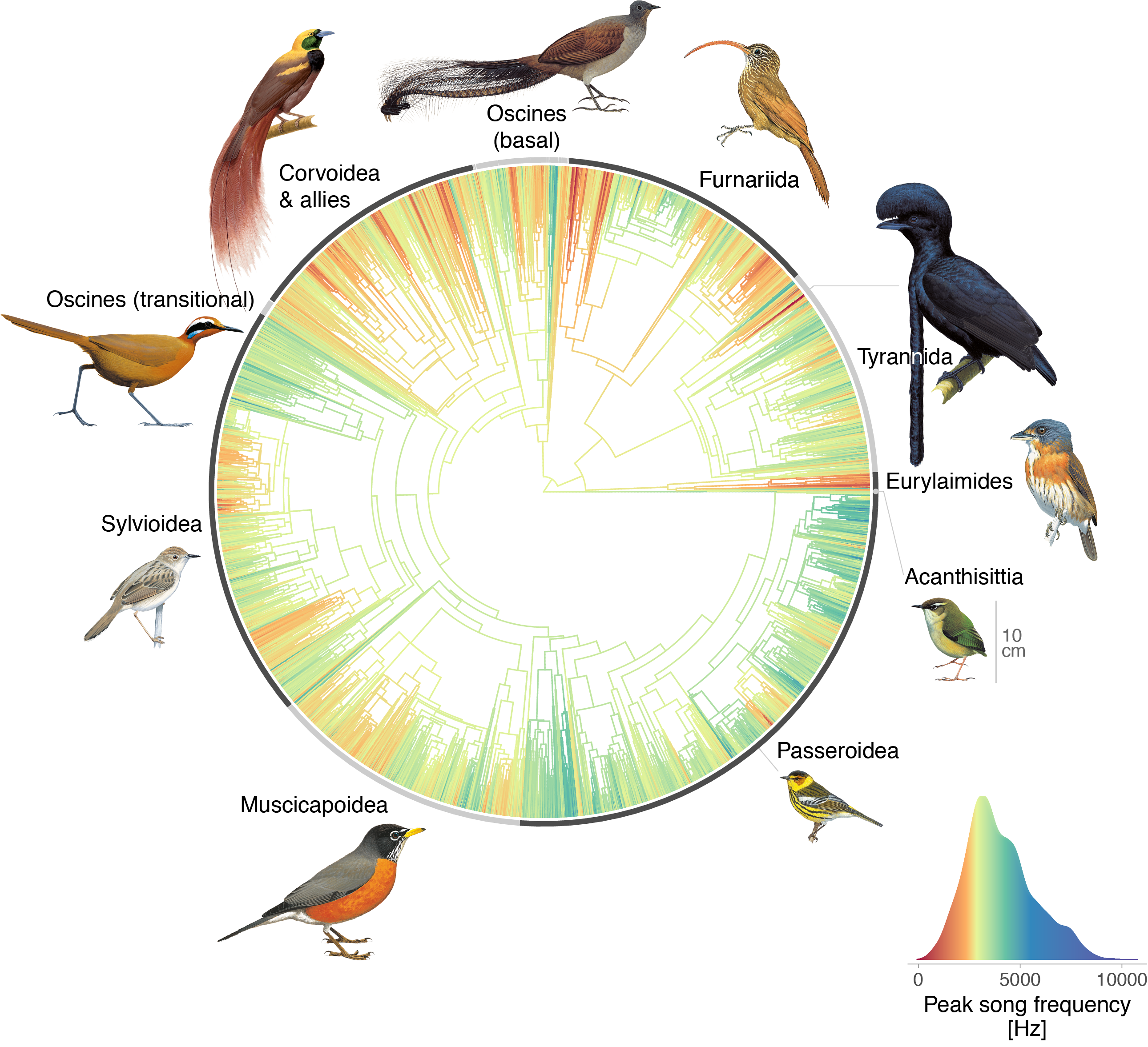

A global analysis of song frequency in passerines provides no support for the acoustic adaptation hypothesis but suggests a role for sexual selectionP. Mikula, M. Valcu, H. Brumm, and 5 more authors2020

A global analysis of song frequency in passerines provides no support for the acoustic adaptation hypothesis but suggests a role for sexual selectionP. Mikula, M. Valcu, H. Brumm, and 5 more authors2020Animals use acoustic signals for communication, implying that the properties of these signals can be under strong selection. The acoustic adaptation hypothesis predicts that species in dense habitats emit lower-frequency sounds than those in open areas because low-frequency sounds propagate further in dense vegetation than high-frequency sounds. Signal frequency may also be under sexual selection because it correlates with body size and lower-frequency sounds are perceived as more intimidating. Here, we evaluate these hypotheses by analysing variation in peak song frequency across 5,085 passerine species (Passeriformes). A phylogenetically informed analysis revealed that song frequency decreases with increasing body mass and with male-biased sexual size dimorphism. However, we found no support for the predicted relationship between frequency and habitat. Our results suggest that the global variation in passerine song frequency is mostly driven by natural and sexual selection causing evolutionary shifts in body size rather than by habitat-related selection on sound propagation.

@article{RN7082, author = {Mikula, P. and Valcu, M. and Brumm, H. and Bulla, M. and Forstmeier, W. and Petruskova, T. and Kempenaers, B. and Albrecht, T.}, journal = {Ecol Lett}, issn = {1461-0248 (Electronic) 1461-023X (Linking)}, doi = {10.1111/ele.13662}, year = {2020}, osf = {https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FA9KY}, type = {Journal Article} }

2019

-

Comment on “Global pattern of nest predation is disrupted by climate change in shorebirds”Martin Bulla, Jeroen Reneerkens, Emily L Weiser, and 56 more authors2019

Comment on “Global pattern of nest predation is disrupted by climate change in shorebirds”Martin Bulla, Jeroen Reneerkens, Emily L Weiser, and 56 more authors2019Kubelka et al. (Reports, 9 November 2018, p. 680) claim that climate change has disrupted patterns of nest predation in shorebirds. They report that predation rates have increased since the 1950s, especially in the Arctic. We describe methodological problems with their analyses and argue that there is no solid statistical support for their claims.

@article{RN6474, author = {Bulla, Martin and Reneerkens, Jeroen and Weiser, Emily L and Sokolov, Aleksandr and Taylor, Audrey R and Sittler, Benoît and McCaffery, Brian J and Ruthrauff, Dan R and Catlin, Daniel H and Payer, David C and Ward, David H. and Solovyeva, Diana V. and Santos, Eduardo S. A. and Rakhimberdiev, Eldar and Nol, Erica and Kwon, Eunbi and Brown, Glen S. and Hevia, Glenda D. and Gates, H. River and Johnson, James A. and van Gils, Jan A. and Hansen, Jannik and Lamarre, Jean-François and Rausch, Jennie and Conklin, Jesse R. and Liebezeit, Joe and Bêty, Joël and Lang, Johannes and Alves, José A. and Fernández-Elipe, Juan and Exo, Klaus-Michael and Bollache, Loïc and Bertellotti, Marcelo and Giroux, Marie-Andrée and van de Pol, Martijn and Johnson, Matthew and Boldenow, Megan L. and Valcu, Mihai and Soloviev, Mikhail and Sokolova, Natalya and Senner, Nathan R. and Lecomte, Nicolas and Meyer, Nicolas and Schmidt, Niels Martin and Gilg, Olivier and Smith, Paul A. and Machín, Paula and McGuire, Rebecca L. and Cerboncini, Ricardo A. S. and Ottvall, Richard and Rob S. A. van Bemmelen, Rose J. Swift and Saalfeld, Sarah T. and Jamieson, Sarah E. and Brown, Stephen and Piersma, Theunis and Albrecht, Tomas and D’Amico, Verónica and Lanctot, Richard B. and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Comment on “Global pattern of nest predation is disrupted by climate change in shorebirds”}, journal = {Science}, volume = {364}, number = {6445}, pages = {eaaw8529}, issn = {0036-8075}, year = {2019}, osf = {https://osf.io/x8fs6/}, type = {Journal Article} } -

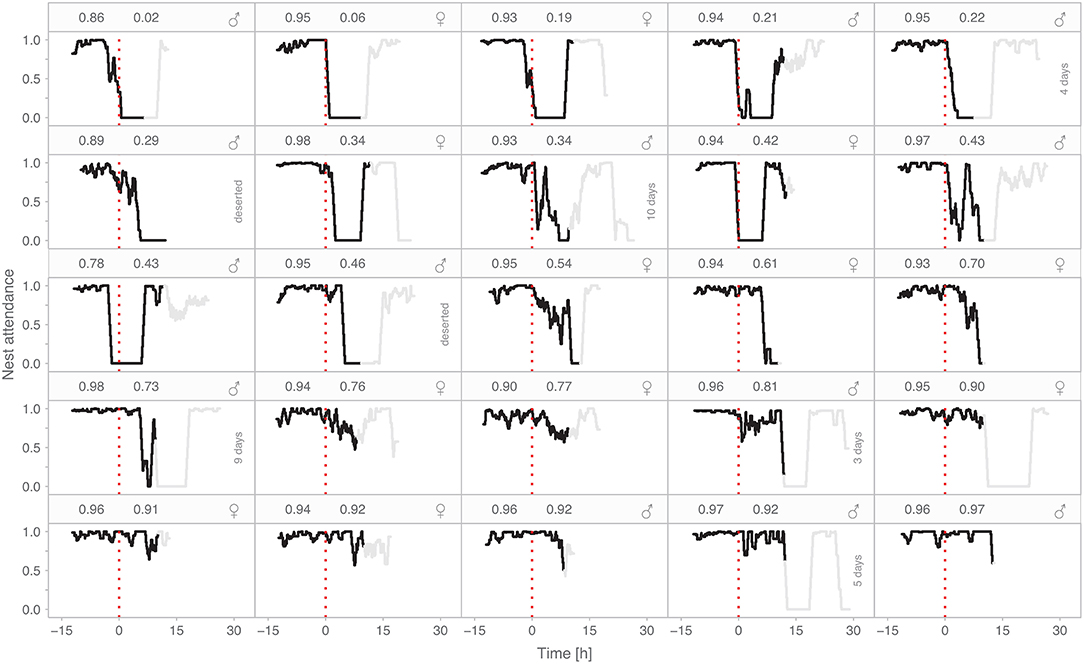

Temporary mate removal during incubation leads to variable compensation in a biparental shorebirdMartin Bulla, Mihai Valcu, Anne L. Rutten, and 1 more author2019

Temporary mate removal during incubation leads to variable compensation in a biparental shorebirdMartin Bulla, Mihai Valcu, Anne L. Rutten, and 1 more author2019Predation is the most common cause of nest failure in birds. While nest predation is relatively well studied in general, our knowledge is unevenly distributed across the globe and taxa, with, for example, limited information on shorebirds breeding in subtropics. Importantly, we know fairly little about the timing of predation within a day. Here, we followed 444 nests of the red-wattled lapwing (Vanellus indicus), a ground-nesting shorebird, for a sum of 7,828 days to estimate a nest predation rate, and continuously monitored 230 of these nests for a sum of 2,779 days to reveal how the timing of predation changes over the day and season in a subtropical desert. We found that 312 nests (70%) hatched, 76 nests (17%) were predated, 23 (5%) failed for other reasons, and 33 (7%) had an unknown fate. Daily predation rate was 0.95% (95%CrI: 0.76% – 1.19%), which for a 30-day long incubation period translates into 25% (20% – 30%) chance of nest being predated. Such a predation rate is low compared to most other avian species. Predation events (N = 25) were evenly distributed across day and night, with a tendency for increased predation around sunrise, and evenly distributed also across the season, although night predation was more common later in the season, perhaps because predators reduce their activity during daylight to avoid extreme heat. Indeed, nests were never predated when midday ground temperatures exceeded 45℃. Whether the diel activity pattern of resident predators undeniably changes across the breeding season and whether the described predation patterns hold for other populations, species, and geographical regions await future investigations.

@article{RN6420, author = {Bulla, Martin and Valcu, Mihai and Rutten, Anne L. and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Temporary mate removal during incubation leads to variable compensation in a biparental shorebird}, journal = {Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution}, volume = {7}, issn = {2296-701X}, doi = {https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00093}, url = {https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00093}, year = {2019}, osf = {https://osf.io/mx82q/}, type = {Journal Article} } -

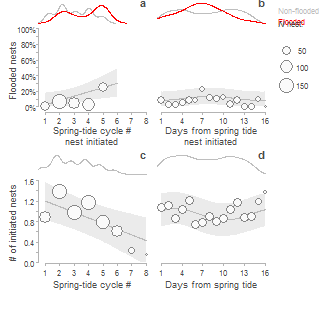

Nest initiation and flooding in response to season and semi-lunar spring tides in a ground-nesting shorebirdSilvia Plaschke, Martin Bulla, Medardo Cruz-López, and 2 more authors2019

Nest initiation and flooding in response to season and semi-lunar spring tides in a ground-nesting shorebirdSilvia Plaschke, Martin Bulla, Medardo Cruz-López, and 2 more authors2019Marine and intertidal organisms face the rhythmic environmental changes induced by tides. The large amplitude of spring tides that occur around full and new moon may threaten nests of ground-nesting birds. These birds face a trade-off between ensuring nest safety from tidal flooding and nesting near the waterline to provide their newly hatched offspring with suitable foraging opportunities. The semi-lunar periodicity of spring tides may enable birds to schedule nest initiation adaptively, for example, by initiating nests around tidal peaks when the water line reaches the farthest into the intertidal habitat. We examined the impact of semi-lunar tidal changes on the phenology of nest flooding and nest initiation in Snowy Plovers (Charadrius nivosus) breeding at Bahía de Ceuta, a coastal wetland in Northwest Mexico. Using nest initiations and fates of 752 nests monitored over ten years we found that the laying season coincides with the lowest spring tides of the year and only 6% of all nests were flooded by tides. Tidal nest flooding varied substantially over time. First, flooding was the primary cause of nest failures in two of the ten seasons indicating high between-season stochasticity. Second, nests were flooded almost exclusively during the second half of the laying season. Third, nest flooding was associated with the semi-lunar spring tide cycle as nests initiated around spring tide had a lower risk of being flooded than nests initiated at other times. Following the spring tide rhythm, plovers appeared to adapt to this risk of flooding with nest initiation rates highest around spring tides and lowest around neap tides.Snowy Plovers appear generally well adapted to the risk of nest flooding by spring tides. Our results are in line with other studies showing that intertidal organisms have evolved adaptive responses to predictable rhythmic tidal changes but these adaptations do not prevent occasional catastrophic losses caused by stochastic events.

@article{RN6451, author = {Plaschke, Silvia and Bulla, Martin and Cruz-López, Medardo and Gómez del Ángel, Salvador and Küpper, Clemens}, title = {Nest initiation and flooding in response to season and semi-lunar spring tides in a ground-nesting shorebird}, journal = {Frontiers in Zoology}, volume = {16}, number = {1}, issn = {1742-9994}, doi = {10.1186/s12983-019-0313-1}, year = {2019}, osf = {https://osf.io/k9n8v/}, type = {Journal Article} } -

Diversity of incubation rhythms in a facultatively uniparental shorebird - the Northern LapwingM. Sladecek, E. Vozabulova, M. E. Salek, and 1 more author2019

Diversity of incubation rhythms in a facultatively uniparental shorebird - the Northern LapwingM. Sladecek, E. Vozabulova, M. E. Salek, and 1 more author2019In birds, incubation by both parents is a common form of care for eggs. Although the involvement of the two parents may vary dramatically between and within pairs, as well as over the course of the day and breeding season, detailed descriptions of this variation are rare, especially in species with variable male contributions to care. Here, we continuously video-monitored 113 nests of Northern Lapwings Vanellus vanellus to reveal the diversity of incubation rhythms and parental involvement, as well as their daily and seasonal variation. We found great between-nest variation in the overall nest attendance (68–94%; median = 87%) and in how much males attended their nests (0–37%; median = 13%). Notably, the less the males attended their nests, the lower was the overall nest attendance, even though females partially compensated for the males’ decrease. Also, despite seasonal environmental trends (e.g. increasing temperature), incubation rhythms changed little over the season and 27-day incubation period. However, as nights shortened with the progressing breeding season, the longest night incubation bout of females shortened too. Importantly, within the 24h-day, nest attendance was highest, incubation bouts longest, exchange gaps shortest and male involvement lowest during the night. Moreover, just after sunrise and before sunset males attended the nest the most. To conclude, we confirm substantial between nest differences in Lapwing male nest attendance, reveal how such differences relates to variation in incubation rhythms, and describe strong circadian incubation rhythms modulated by sunrise and sunset.

@article{RN6385, author = {Sladecek, M. and Vozabulova, E. and Salek, M. E. and Bulla, M.}, title = {Diversity of incubation rhythms in a facultatively uniparental shorebird - the Northern Lapwing}, journal = {Sci Rep}, volume = {9}, number = {1}, pages = {4706}, issn = {2045-2322 (Electronic) 2045-2322 (Linking)}, doi = {10.1038/s41598-019-41223-z}, url = {https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30886196}, year = {2019}, osf = {http://osf.io/y4vpe}, type = {Journal Article} } -

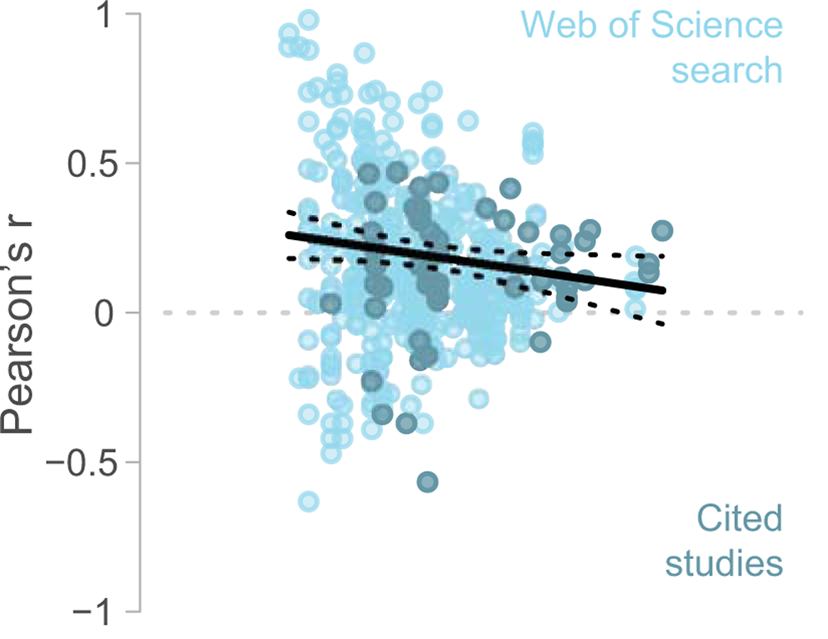

Scrutinizing assortative mating in birdsD. Wang, W. Forstmeier, M. Valcu, and 8 more authors2019

Scrutinizing assortative mating in birdsD. Wang, W. Forstmeier, M. Valcu, and 8 more authors2019It is often claimed that pair bonds preferentially form between individuals that resemble one another. Such assortative mating appears to be widespread throughout the animal kingdom. Yet it is unclear whether the apparent ubiquity of assortative mating arises primarily from mate choice (“like attracts like”), which can be constrained by same-sex competition for mates; from spatial or temporal separation; or from observer, reporting, publication, or search bias. Here, based on a conventional literature search, we find compelling meta-analytical evidence for size-assortative mating in birds (r = 0.178, 95% CI 0.142–0.215, 83 species, 35,591 pairs). However, our analyses reveal that this effect vanishes gradually with increased control of confounding factors. Specifically, the effect size decreased by 42% when we used previously unpublished data from nine long-term field studies, i.e., data free of reporting and publication bias (r = 0.103, 95% CI 0.074–0.132, eight species, 16,611 pairs). Moreover, in those data, assortative mating effectively disappeared when both partners were measured by independent observers or separately in space and time (mean r = 0.018, 95% CI −0.016–0.057). Likewise, we also found no evidence for assortative mating in a direct experimental test for mutual mate choice in captive populations of Zebra finches (r = −0.020, 95% CI −0.148–0.107, 1,414 pairs). These results highlight the importance of unpublished data in generating unbiased meta-analytical conclusions and suggest that the apparent ubiquity of assortative mating reported in the literature is overestimated and may not be driven by mate choice or mating competition for preferred mates

@article{RN6372, author = {Wang, D. and Forstmeier, W. and Valcu, M. and Dingemanse, N. J. and Bulla, M. and Both, C. and Duckworth, R. A. and Kiere, L. M. and Karell, P. and Albrecht, T. and Kempenaers, B.}, title = {Scrutinizing assortative mating in birds}, journal = {PLoS Biol}, volume = {17}, number = {2}, pages = {e3000156}, issn = {1545-7885 (Electronic) 1544-9173 (Linking)}, doi = {10.1371/journal.pbio.3000156}, url = {https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30789896}, year = {2019}, type = {Journal Article} }

2017

- Phyl TransMethods in field chronobiologyD. M. Dominoni, S. Akesson, R. Klaassen, and 2 more authors2017

Chronobiological research has seen a continuous development of novel approaches and techniques to measure rhythmicity at different levels of biological organization from locomotor activity (e.g. migratory restlessness) to physiology (e.g. temperature and hormone rhythms, and relatively recently also in genes, proteins and metabolites). However, the methodological advancements in this field have been mostly and sometimes exclusively used only in indoor laboratory settings. In parallel, there has been an unprecedented and rapid improvement in our ability to track animals and their behaviour in the wild. However, while the spatial analysis of tracking data is widespread, its temporal aspect is largely unexplored. Here, we review the tools that are available or have potential to record rhythms in the wild animals with emphasis on currently overlooked approaches and monitoring systems. We then demonstrate, in three question-driven case studies, how the integration of traditional and newer approaches can help answer novel chronobiological questions in free-living animals. Finally, we highlight unresolved issues in field chronobiology that may benefit from technological development in the future. As most of the studies in the field are descriptive, the future challenge lies in applying the diverse technologies to experimental set-ups in the wild.

@article{RN5955, author = {Dominoni, D. M. and Akesson, S. and Klaassen, R. and Spoelstra, K. and Bulla, M.}, title = {Methods in field chronobiology}, journal = {Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci}, volume = {372}, number = {1734}, issn = {1471-2970 (Electronic) 0962-8436 (Linking)}, doi = {10.1098/rstb.2016.0247}, url = {https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28993491}, year = {2017}, osf = {https://osf.io/wxufm/}, type = {Journal Article} } - Phyl TransMarine biorhythms: bridging chronobiology and ecologyM. Bulla, T. Oudman, A. I. Bijleveld, and 2 more authors2017

Marine organisms adapt to complex temporal environments that include daily, tidal, semi-lunar, lunar and seasonal cycles. However, our understanding of marine biological rhythms and their underlying molecular basis is mainly confined to a few model organisms in rather simplistic laboratory settings. Here, we use new empirical data and recent examples of marine biorhythms to highlight how field ecologists and laboratory chronobiologists can complement each other’s efforts. First, with continuous tracking of intertidal shorebirds in the field, we reveal individual differences in tidal and circadian foraging rhythms. Second, we demonstrate that shorebird species that spend 8–10 months in tidal environments rarely maintain such tidal or circadian rhythms during breeding, likely because of other, more pertinent, temporally structured, local ecological pressures such as predation or social environment. Finally, we use examples of initial findings from invertebrates (arthropods and polychaete worms) that are being developed as model species to study the molecular bases of lunar-related rhythms. These examples indicate that canonical circadian clock genes (i.e. the homologous clock genes identified in many higher organisms) may not be involved in lunar/tidal phenotypes. Together, our results and the examples we describe emphasize that linking field and laboratory studies is likely to generate a better ecological appreciation of lunar-related rhythms in the wild.

@article{RN5935, author = {Bulla, M. and Oudman, T. and Bijleveld, A. I. and Piersma, T. and Kyriacou, C. P.}, title = {Marine biorhythms: bridging chronobiology and ecology}, journal = {Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci}, volume = {372}, number = {1734}, issn = {1471-2970 (Electronic) 0962-8436 (Linking)}, doi = {10.1098/rstb.2016.0253}, url = {https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28993497}, year = {2017}, osf = {https://osf.io/xby9t/}, type = {Journal Article} } -

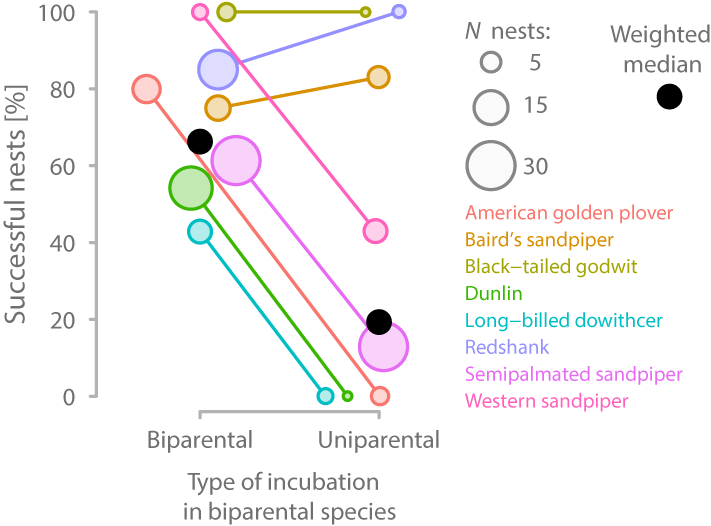

Flexible parental care: Uniparental incubation in biparentally incubating shorebirdsMartin Bulla, Hanna Prüter, Hana Vitnerová, and 5 more authors2017

Flexible parental care: Uniparental incubation in biparentally incubating shorebirdsMartin Bulla, Hanna Prüter, Hana Vitnerová, and 5 more authors2017The relative investment of females and males into parental care might depend on the population’s adult sex-ratio. For example, all else being equal, males should be the more caring sex if the sex-ratio is male biased. Whether such outcomes are evolutionary fixed (i.e. related to the species’ typical sex-ratio) or whether they arise through flexible responses of individuals to the current population sex-ratio remains unclear. Nevertheless, a flexible response might be limited by the evolutionary history of the species, because one sex may have lost the ability to care or because a single parent cannot successfully raise the brood. Here, we demonstrate that after the disappearance of one parent, individuals from 8 out of 15 biparentally incubating shorebird species were able to incubate uniparentally for 1–19 days (median = 3, N = 69). Moreover, their daily incubation rhythm often resembled that of obligatory uniparental shorebird species. Although it has been suggested that in some biparental shorebirds females desert their brood after hatching, we found both sexes incubating uniparentally. Strikingly, in 27% of uniparentally incubated clutches - from 5 species - we documented successful hatching. Our data thus reveal the potential for a flexible switch from biparental to uniparental care.

@article{RN5936, author = {Bulla, Martin and Prüter, Hanna and Vitnerová, Hana and Tijsen, Wim and Sládeček, Martin and Alves, José A. and Gilg, Olivier and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Flexible parental care: Uniparental incubation in biparentally incubating shorebirds}, journal = {Scientific Reports}, volume = {7}, number = {1}, issn = {2045-2322}, doi = {http://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13005-y}, year = {2017}, osf = {https://osf.io/3rsny}, type = {Journal Article} }

2016

-

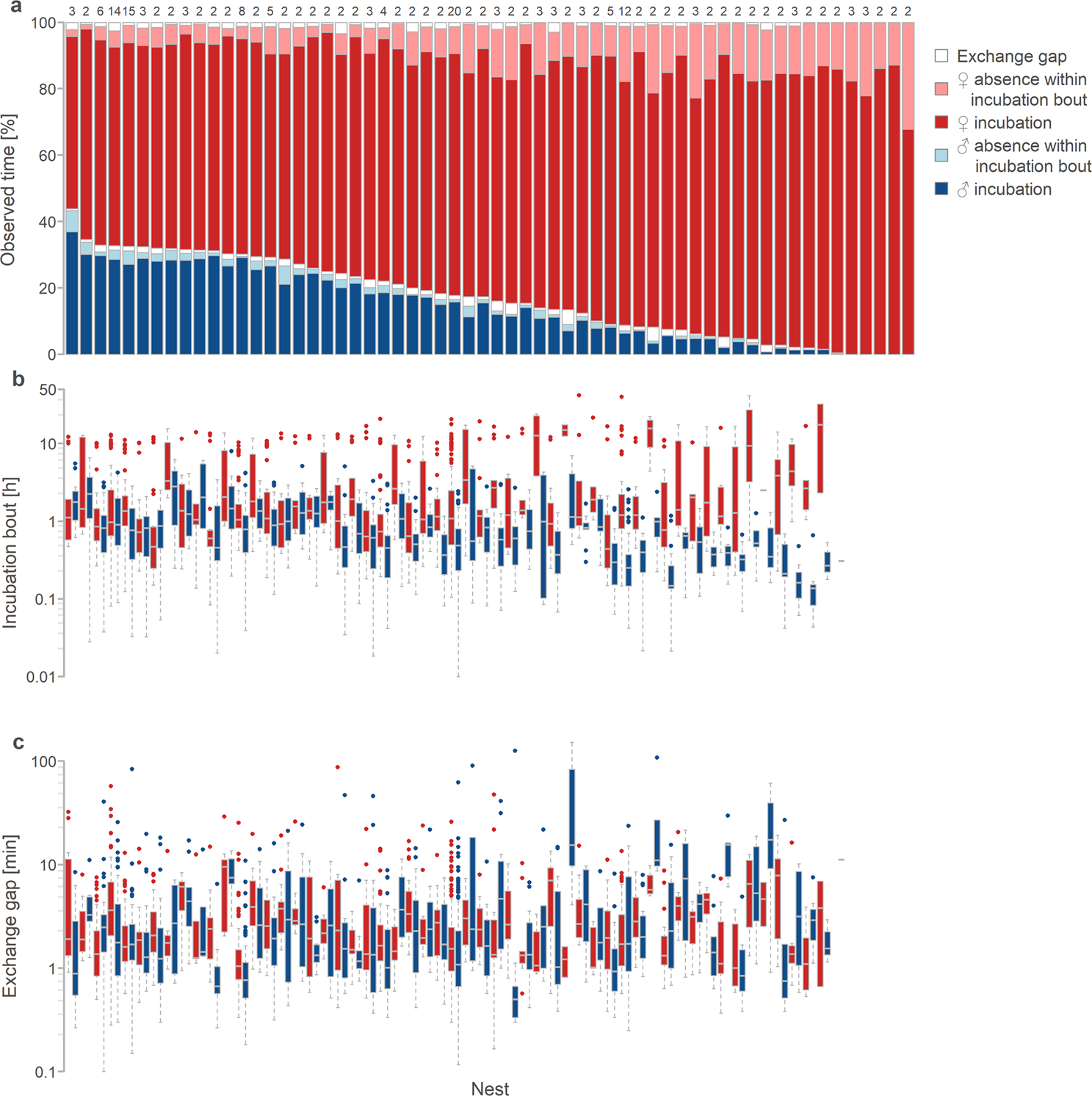

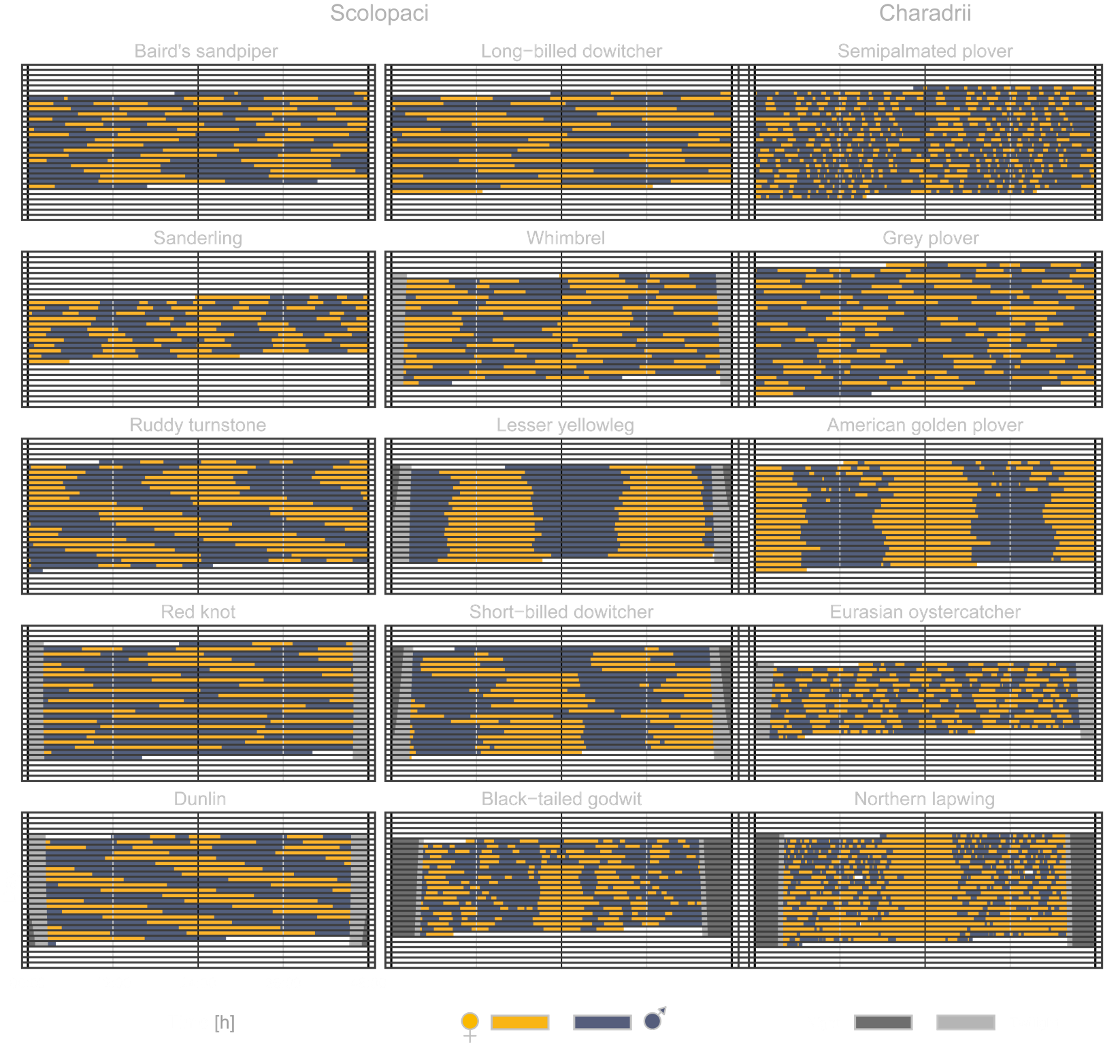

Unexpected diversity in socially synchronized rhythms of shorebirdsMartin Bulla, Mihai Valcu, Adriaan M. Dokter, and 73 more authors2016

Unexpected diversity in socially synchronized rhythms of shorebirdsMartin Bulla, Mihai Valcu, Adriaan M. Dokter, and 73 more authors2016@article{RN5395, author = {Bulla, Martin and Valcu, Mihai and Dokter, Adriaan M. and Dondua, Alexei G. and Kosztolányi, András and Rutten, Anne L. and Helm, Barbara and Sandercock, Brett K. and Casler, Bruce and Ens, Bruno J. and Spiegel, Caleb S. and Hassell, Chris J. and Küpper, Clemens and Minton, Clive and Burgas, Daniel and Lank, David B. and Payer, David C. and Loktionov, Egor Y. and Nol, Erica and Kwon, Eunbi and Smith, Fletcher and Gates, H. River and Vitnerová, Hana and Prüter, Hanna and Johnson, James A. and St Clair, James J. H. and Lamarre, Jean-François and Rausch, Jennie and Reneerkens, Jeroen and Conklin, Jesse R. and Burger, Joanna and Liebezeit, Joe and Bêty, Joël and Coleman, Jonathan T. and Figuerola, Jordi and Hooijmeijer, Jos C. E. W. and Alves, José A. and Smith, Joseph A. M. and Weidinger, Karel and Koivula, Kari and Gosbell, Ken and Exo, Klaus-Michael and Niles, Larry and Koloski, Laura and McKinnon, Laura and Praus, Libor and Klaassen, Marcel and Giroux, Marie-Andrée and Sládeček, Martin and Boldenow, Megan L. and Goldstein, Michael I. and Šálek, Miroslav and Senner, Nathan and Rönkä, Nelli and Lecomte, Nicolas and Gilg, Olivier and Vincze, Orsolya and Johnson, Oscar W. and Smith, Paul A. and Woodard, Paul F. and Tomkovich, Pavel S. and Battley, Phil F. and Bentzen, Rebecca and Lanctot, Richard B. and Porter, Ron and Saalfeld, Sarah T. and Freeman, Scott and Brown, Stephen C. and Yezerinac, Stephen and Székely, Tamás and Montalvo, Tomás and Piersma, Theunis and Loverti, Vanessa and Pakanen, Veli-Matti and Tijsen, Wim and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Unexpected diversity in socially synchronized rhythms of shorebirds}, journal = {Nature}, volume = {540}, number = {7631}, pages = {109-113}, issn = {0028-0836}, doi = {http://doi.org/10.1038/nature20563}, url = {http:https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature20563}, year = {2016}, abastract = {The behavioural rhythms of organisms are thought to be under strong selection, influenced by the rhythmicity of the environment1,2,3,4. Such behavioural rhythms are well studied in isolated individuals under laboratory conditions1,5, but free-living individuals have to temporally synchronize their activities with those of others, including potential mates, competitors, prey and predators6,7,8,9,10. Individuals can temporally segregate their daily activities (for example, prey avoiding predators, subordinates avoiding dominants) or synchronize their activities (for example, group foraging, communal defence, pairs reproducing or caring for offspring)6,7,8,9,11. The behavioural rhythms that emerge from such social synchronization and the underlying evolutionary and ecological drivers that shape them remain poorly understood5,6,7,9. Here we investigate these rhythms in the context of biparental care, a particularly sensitive phase of social synchronization12 where pair members potentially compromise their individual rhythms. Using data from 729 nests of 91 populations of 32 biparentally incubating shorebird species, where parents synchronize to achieve continuous coverage of developing eggs, we report remarkable within- and between-species diversity in incubation rhythms. Between species, the median length of one parent’s incubation bout varied from 1–19 h, whereas period length—the time in which a parent’s probability to incubate cycles once between its highest and lowest value—varied from 6–43 h. The length of incubation bouts was unrelated to variables reflecting energetic demands, but species relying on crypsis (the ability to avoid detection by other animals) had longer incubation bouts than those that are readily visible or who actively protect their nest against predators. Rhythms entrainable to the 24-h light–dark cycle were less prevalent at high latitudes and absent in 18 species. Our results indicate that even under similar environmental conditions and despite 24-h environmental cues, social synchronization can generate far more diverse behavioural rhythms than expected from studies of individuals in captivity5,6,7,9. The risk of predation, not the risk of starvation, may be a key factor underlying the diversity in these rhythms.}, osf = {http://osf.io/wxufm/}, type = {Journal Article} }

2015

-

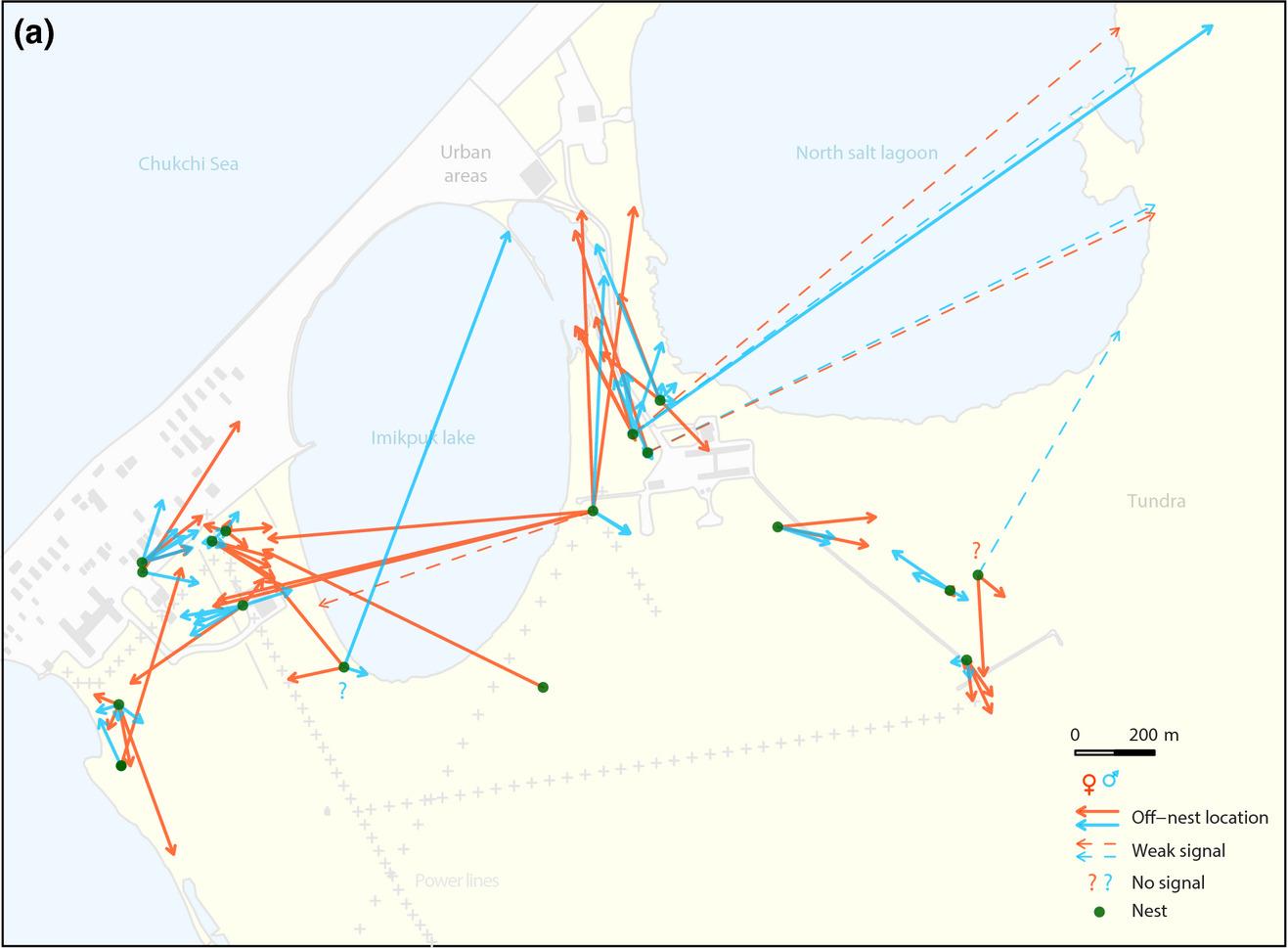

Off-nest behaviour in a biparentally incubating shorebird varies with sex, time of day and weatherMartin Bulla, Elias Stich, Mihai Valcu, and 1 more author2015

Off-nest behaviour in a biparentally incubating shorebird varies with sex, time of day and weatherMartin Bulla, Elias Stich, Mihai Valcu, and 1 more author2015@article{RN4482, author = {Bulla, Martin and Stich, Elias and Valcu, Mihai and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Off-nest behaviour in a biparentally incubating shorebird varies with sex, time of day and weather}, journal = {Ibis}, volume = {157}, number = {3}, pages = {575-589}, issn = {1474-919X}, doi = {http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12276}, url = {http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12276}, year = {2015}, abastract = {Biparental incubation is a form of cooperation between parents, but it is not conflict-free because parents trade off incubation against other activities (e.g. self-maintenance, mating opportunities). How parents resolve such conflict and achieve cooperation remains unknown. To understand better the potential for conflict, cooperation and the constraints on incubation behaviour, investigation of the parents' behaviour, both during incubation and when they are off incubation-duty, is necessary. Using a combination of automated incubation-monitoring and radiotelemetry we simultaneously investigated the behaviours of both parents in the biparentally incubating Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla, a shorebird breeding under continuous daylight in the high Arctic. Here, we describe the off-nest behaviour of 32 off-duty parents from 17 nests. Off-duty parents roamed on average 224 m from their nest, implying that direct communication with the incubating partner is unlikely. On average, off-duty parents spent only 59% of their time feeding. Off-nest distance and behaviour (like previously reported incubation behaviour) differed between the sexes, and varied with time and weather. Males roamed less far from the nest and spent less time feeding than did females. At night, parents stayed closer to the nest and tended to spend less time feeding than during the day. Further exploratory analyses revealed that the time spent feeding increased over the incubation period, and that at night, but not during the day, off-duty parents spent more time feeding under relatively windy conditions. Hence, under energetically stressful conditions, parents may be forced to feed more. Our results suggest that parents are likely to conflict over the favourable feeding times, i.e. over when to incubate (within a day or incubation period). Our study also indicates that Semipalmated Sandpiper parents do not continuously keep track of each other to optimize incubation scheduling and, hence, that the off-duty parent's decision to remain closer to the nest drives the length of incubation bouts.}, type = {Journal Article} } -

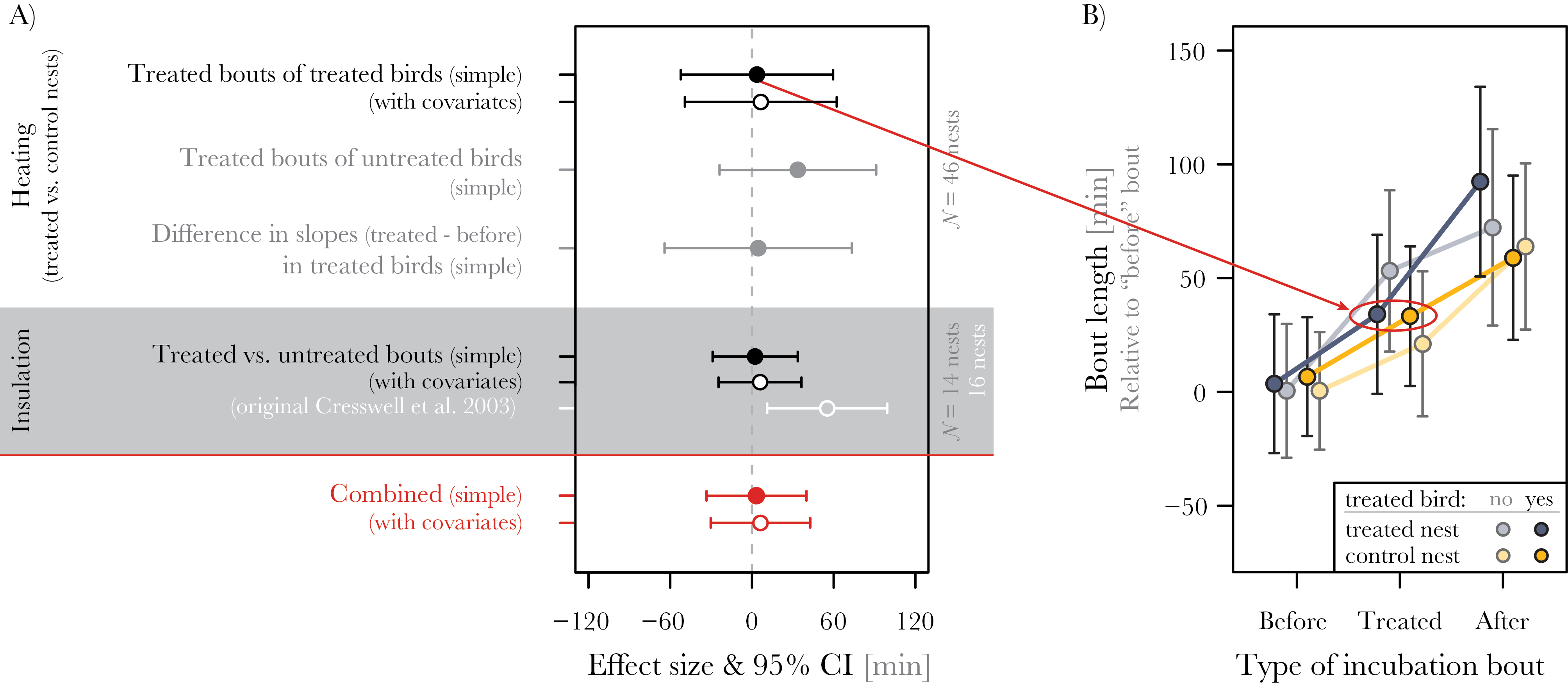

Biparental incubation-scheduling: no experimental evidence for major energetic constraintsMartin Bulla, Will Cresswell, Anne L. Rutten, and 2 more authors2015

Biparental incubation-scheduling: no experimental evidence for major energetic constraintsMartin Bulla, Will Cresswell, Anne L. Rutten, and 2 more authors2015@article{RN4295, author = {Bulla, Martin and Cresswell, Will and Rutten, Anne L. and Valcu, Mihai and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Biparental incubation-scheduling: no experimental evidence for major energetic constraints}, journal = {Behavioral Ecology}, volume = {26}, number = {1}, pages = {30-37}, doi = {http://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/aru156}, year = {2015}, abastract = {Incubation is energetically demanding, but it is debated whether these demands constrain incubation-scheduling (i.e., the length, constancy, and timing of incubation bouts) in cases where both parents incubate. Using 2 methods, we experimentally reduced the energetic demands of incubation in the semipalmated sandpiper, a biparental shorebird breeding in the harsh conditions of the high Arctic. First, we decreased the demands of incubation for 1 parent only by exchanging 1 of the 4 eggs for an artificial egg that heated up when the focal bird incubated. Second, we reanalyzed the data from the only published experimental study that has explicitly tested energetic constraints on incubation-scheduling in a biparentally incubating species ( Cresswell et al. 2003 ). In this experiment, the energetic demands of incubation were decreased for both parents by insulating the nest cup. We expected that the treated birds, in both experiments, would change the length of their incubation bouts, if biparental incubation-scheduling is energetically constrained. However, we found no evidence that heating or insulation of the nest affected the length of incubation bouts: the combined effect of both experiments was an increase in bout length of 3.6min (95% CI: −33 to 40), which is equivalent to a 0.5% increase in the length of the average incubation bout. These results demonstrate that the observed biparental incubation-scheduling in semipalmated sandpipers is not primarily driven by energetic constraints and therefore by the state of the incubating bird, implying that we still do not understand the factors driving biparental incubation-scheduling.}, type = {Journal Article} }

2014

-

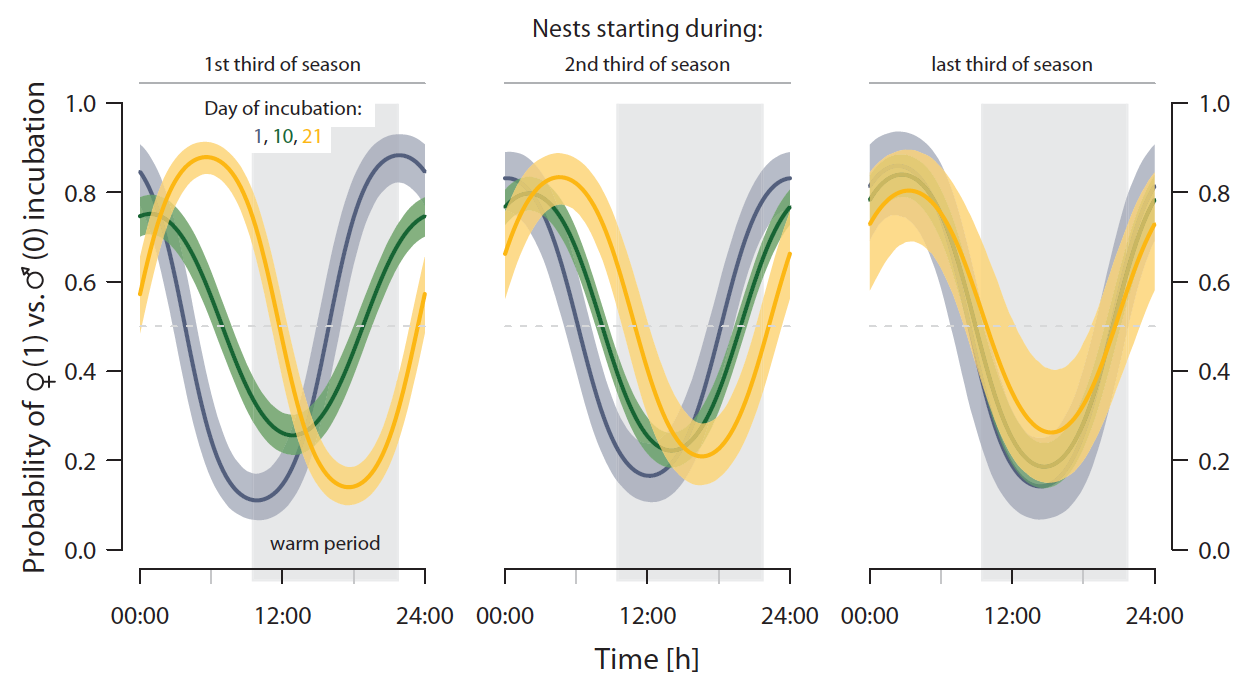

Biparental incubation patterns in a high-Arctic breeding shorebird: how do pairs divide their duties?Martin Bulla, Mihai Valcu, Anne L. Rutten, and 1 more author2014

Biparental incubation patterns in a high-Arctic breeding shorebird: how do pairs divide their duties?Martin Bulla, Mihai Valcu, Anne L. Rutten, and 1 more author2014@article{RN3403, author = {Bulla, Martin and Valcu, Mihai and Rutten, Anne L. and Kempenaers, Bart}, title = {Biparental incubation patterns in a high-Arctic breeding shorebird: how do pairs divide their duties?}, journal = {Behavioral Ecology}, volume = {25}, number = {1}, pages = {152-164}, doi = {http://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/art098}, year = {2014}, abastract = {In biparental species, parents may be in conflict over how much they invest into their offspring. To understand this conflict, parental care needs to be accurately measured, something rarely done. Here, we quantitatively describe the outcome of parental conflict in terms of quality, amount, and timing of incubation throughout the 21-day incubation period in a population of semipalmated sandpipers (Calidris pusilla) breeding under continuous daylight in the high Arctic. Incubation quality, measured by egg temperature and incubation constancy, showed no marked difference between the sexes. The amount of incubation, measured as length of incubation bouts, was on average 51min longer per bout for females (11.5h) than for males (10.7h), at first glance suggesting that females invested more than males. However, this difference may have been offset by sex differences in the timing of incubation; females were more often off nest during the warmer period of the day, when foraging conditions were presumably better. Overall, the daily timing of incubation shifted over the incubation period (e.g., for female incubation from evening–night to night–morning) and over the season, but varied considerably among pairs. At one extreme, pairs shared the amount of incubation equally, but one parent always incubated during the colder part of the day; at the other extreme, pairs shifted the start of incubation bouts between days so that each parent experienced similar conditions across the incubation period. Our results highlight how the simultaneous consideration of different aspects of care across time allows sex-specific investment to be more accurately quantified.}, type = {Journal Article} }

2012

-

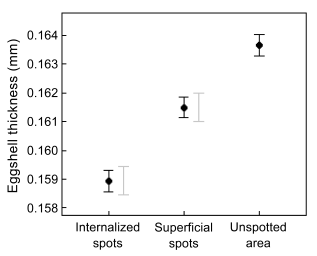

Eggshell spotting does not predict male incubation but marks thinner areas of a shorebird’s shells (Las Manchas en las Cáscaras no Predicen la Incubación por los Machos pero Demarcan Áreas más Delgadas en los Huevos de un Ave Playera)Martin Bulla, Miroslav Šálek, and Andrew G. Gosler2012

Eggshell spotting does not predict male incubation but marks thinner areas of a shorebird’s shells (Las Manchas en las Cáscaras no Predicen la Incubación por los Machos pero Demarcan Áreas más Delgadas en los Huevos de un Ave Playera)Martin Bulla, Miroslav Šálek, and Andrew G. Gosler2012@article{RN2810, author = {Bulla, Martin and Šálek, Miroslav and Gosler, Andrew G.}, title = {Eggshell spotting does not predict male incubation but marks thinner areas of a shorebird's shells (Las Manchas en las Cáscaras no Predicen la Incubación por los Machos pero Demarcan Áreas más Delgadas en los Huevos de un Ave Playera)}, journal = {The Auk}, volume = {129}, number = {1}, pages = {26-35}, issn = {00048038}, url = {http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/auk.2012.11090}, year = {2012}, type = {Journal Article} } -

Unusual incubation: Long-billed Dowitcher incubates mammalian bonesL. A. Langlois, K. Murböck, M. Bulla, and 1 more author2012

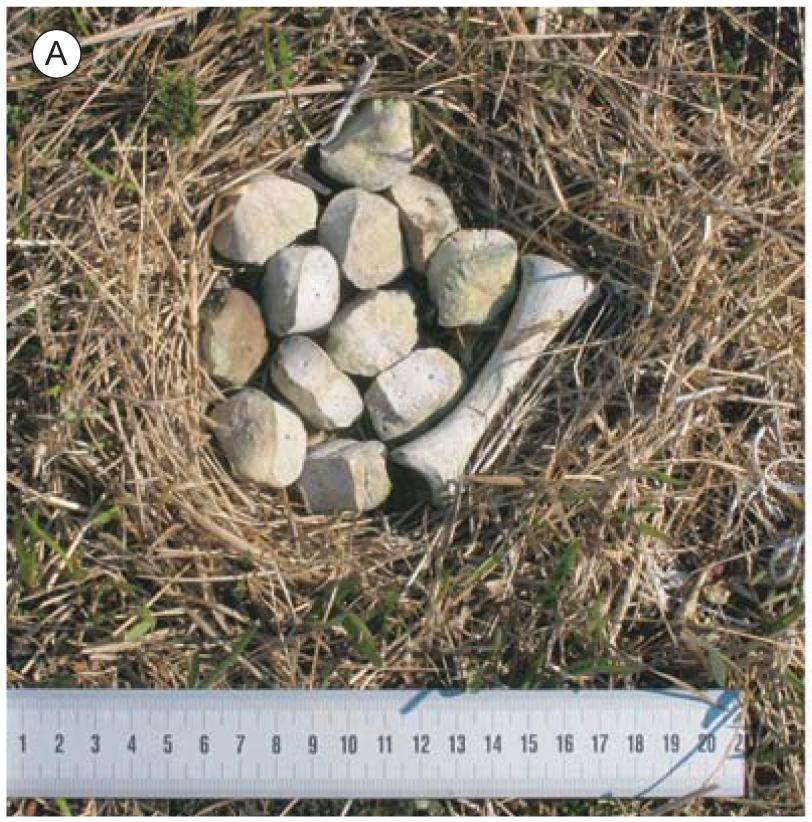

Unusual incubation: Long-billed Dowitcher incubates mammalian bonesL. A. Langlois, K. Murböck, M. Bulla, and 1 more author2012@article{RN2998, author = {Langlois, L. A. and Murböck, K. and Bulla, M. and Kempenaers, B.}, title = {Unusual incubation: Long-billed Dowitcher incubates mammalian bones}, journal = {Ardea}, volume = {100}, number = {2}, pages = {206-210}, year = {2012}, abastract = {It is well established that once birds have laid their eggs they sometimes incubate non-egg objects. However, reports of birds incubating solely non-egg objects (without prior manipulation by researchers) are rare. Here we report on our observation of a Long-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus scolopaceus incubating a clutch composed entirely of mammalian bones. To our knowledge, this is the first report on (a) incubation of foreign objects in Scolopacidae, (b) incubation of a ‘clutch’ composed entirely of bones, and (c) incubation of foreign objects in a nest atypical for this species in both construction and nest habitat. We discuss possible explanations for this presumably maladaptive behaviour.}, type = {Journal Article} }

2006

- E J MarketingMarketing and non-profit organizations in the Czech RepublicM. Bulla, and D. Starr-Glass2006

@article{RN1511, author = {Bulla, M. and Starr-Glass, D.}, title = {Marketing and non-profit organizations in the Czech Republic}, journal = {European Journal of Marketing}, volume = {40}, number = {1/2}, pages = {130-144}, issn = {0309-0566}, doi = {10.1108/03090560610637356}, year = {2006}, abastract = {Purpose This paper aims to examine the context and nature of marketing used by nonprofit organizations in the Czech Republic. Design/methodology/approach A number of senior self‐designated marketing managers in a wide range of non‐profit organizations in Prague were interviewed to generate a descriptive narrative of what these key persons understood marketing to be and how they devised and implemented marketing within organizational strategy. Findings The findings paralleled that of other research (1995‐2005) on the understanding and role of marketing within the profit sector of the Czech Republic. While marketing was identified as an interesting and powerful concept, non‐profit policy makers generally had a limited understanding of a marketing theory or of the context in which exchange transactions occurred. Research limitations/implications This project was designed as an initial survey. The limited number of representatives interviewed and their purposeful selection from a small number of high‐profile non‐profit organizations limit the reliability of the findings and reduce the extent to which they can be generalized. Practical implications This paper provides a useful entry point for those interested in the use of marketing in the Czech Republic, a very significant transformative economy in the centre of Europe. Since one of the authors is a native Czech speaker, the paper reviews relevant marketing and non‐profit literature in Czech as well as English. Originality/value While there has been some interest in the understanding and practice of marketing in the profit sector, it is believed that this is the first paper to address the non‐profit sector – a sector that plays a very significant role within transformative economies.}, type = {Journal Article} }